Traditional Sake Brewing

traditional sake brewing

Here we'd like to introduce the basic process of traditional Japanese sake brewing, listed by UNESCO in December 2024 as Intangible Cultural Heritage. Some elements may change depending on region and brewery, such as techniques, the number of shikomi steps used, the usage of pasteurization, and so on.

Polishing rice

Rice milling

The milling of brown sake rice such as Yamadanishiki, which Hyogo Prefecture is a major producer of. As proteins and other elements found in rice can lead to off flavors, thirty percent or more of each grain is generally milled away. This is also known as 'rice polishing,' and certain designations such as daiginjo and ginjo are given depending on the level of polishing.

Washing and steaming rice

Rice washing, soaking, steaming, and cooling

After the rice is milled, it is washed with water to remove bran and grime, then soaked for a period of time. As the amount of water absorbed by the rice can change based on its type, its milling rate, temperature (water temperature), and humidity, this amount of time is adjusted while taking all of these factors into account. After soaking, the rice is steamed in a large tub called a koshiki. Factors such as temperature are also considered during this step, so volume and temperature are adjusted. The steamed rice is then cooled to different temperatures depending on its use, such as to make koji, shubo yeast starter, or kake-mai.

Steamed rice turning into rice koji

Making koji

On its own, rice does not contain sugars and cannot ferment into alcohol. This is why koji mold is used to turn the starch within the rice into sugars. Koji is made by applying koji mold to steamed rice and allowing it to propagate. However, koji mold generates heat in the process of propagating. If left to itself, it will reach temperatures of over 50 degrees Celsius and die. On the other hand, it will stop working if the temperature is too cold. For this reason, proper temperature control is incredibly important during the two days it takes to make the koji.

Creating the sake starter

Making shubo

Yeast, lactic acid bacteria, and steamed rice are added to a combination of the koji created in step 3 and water to create shubo, or the starter. The lactic acid bacteria plays a role in killing any unwanted bacteria that could interfere with the yeast. While refined lactic acid is used now, this was done in the past by propagating wild lactic acid bacteria present in the area. This traditional method is known as the kimoto method.

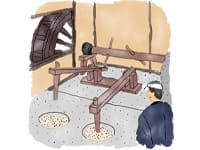

Adding ingredients over three steps

Creating the moromi

Ingredients (steamed rice, koji, and water) are added once more to the starter in order to ferment into alcohol, creating the moromi. Adding all of the ingredients at once will lessen the concentration of the carefully created starter, decreasing the speed of the yeast's propagation as well. This leads to the amount of unwanted bacteria increasing within a cask that can no longer maintain the correct acidity. For that reason, ingredients are added over multiple stages while keeping an eye on the starter. It's important to allow the ingredients to slowly ferment. The three-step shikomi is the most widely used, which generally involves a gradual increase in the amount added over three steps. The first step is known as soe-jikomi, the second as naka-jikomi, and the third as tome-jikomi. The day following the soe-jikomi is known as the odori, where the ingredients are left alone for one day in order to promote yeast propagation. Following the four-day three-step shikomi, three to four weeks are then spent promoting alcoholic fermentation of the moromi.

Press and filter and you're nearly don

Pressing, filtering, pasteurization, storage

Once the moromi is finished fermenting, it is stuffed in a bag and pressed. The liquids (sake) and solids (sake lees) are separated at this stage. The liquids are filtered through a material such as activated charcoal to produce a transparent sake worthy of the name seishu (refined sake). It is then heat treated in order to pasteurize the sake and stabilize its quality before it is stored for a time. However, there are some sake that are never heated, such as unpasteurized sake (nama-zake).

Final steps determined by brand

Blending, dilution, pasteurization, bottling

After the sake has mellowed in storage for six to twelve months, it is heated once more, packaged into bottles or cartons, and sent to stores. Elements may differ even among different sake from the same brewery, such as storage times, or the addition of brewer's alcohol and water, changing the flavor and alcohol content to create products and brands with different characteristics.

Source: Sakamizukihttps://www.sawanotsuru.co.jp/site/nihonshu-columm/